Denis Clarke-Hall

Denis Lucian Clarke-Hall, FRIBA (4 July 1910 - 31 July 2006) was an architect who pioneered new standards in post-war school design. He served as President of the Architectural Association (AA) 1958-59 and as Chairman of the Architects' Registration Council of the United Kingdom between 1963-64.

Born in Essex in 1910, he was the son of Sir William Clarke-Hall and Edna Clarke-Hall (née Waugh). His father was a magistrate, who with the barrister Benjamin Waugh, founded the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC). His mother was a renowned artist, often using her two sons as her subjects.

He was educated at Bedales School and King's College London (only to find the course disappointing and to leave after a year). His father sent him to the newly opened National Institute of Industrial Psychology, which recommended architecture as appropriate to his mix of scientific and woodworking skills. So, in 1930 he began his architectural studies at the Architectural Association, which was to become the most progressive architecture school in Britain by 1940 but which in 1930 was still largely traditional. His final-year dissertation at the AA was on the uses and applications of concrete, when he was advised by the engineer Ove Arup, then a studio tutor.

On leaving the AA in 1936, he went to work for Clive Entwistle, who introduced him to the Modern Architectural Research Group (MARS) - the vanguard of British modernism. In 1937, having just qualified as an architect, he won a competition sponsored by the progressive News Chronicle for an ideal secondary school. This was well in advance of the reforms in the 1940s that made secondary education universal. For his competition submission, he spent six weeks researching classroom design, including angles of view, lighting and heating, with Ove Arup advising him on the structure. The News Chronicle design was entirely drawn from first principles and the competition win secured his career as a specialist schools' architect.

He was commissioned by the Education Officer for the North Riding of Yorkshire to realise a version of his design as the Richmond Girls' High School (now the sixth form centre of Richmond School). It was a rare example of the 1930s Modern Movement in northern England. The design combined load-bearing walls of local stone with concrete construction, realising a synthesis of modern and traditional elements that marked a distinctive progression for British architecture. The school was completed in 1940, its windows arriving miraculously from Switzerland and with stacking furniture designed by Alvar Aalto.

The design of Richmond High School was revolutionary at the time. Classrooms were grouped together as pairs that formed a pavilion set off a main circulation spine, creating an enclosed courtyard. Large south-facing windows were designed to be folded away, allowing summer classes to take place outside. A sliding wall between the assembly space and entrance meant that a larger space could be created for community functions. The colour scheme was also revolutionary. At a time when the standard school colours were cream, green and brown, he pushed for a modern palette: pastel colours with white painted woodwork, and crimson ceilings for smaller rooms.

Richmond High School’s architectural significance in pioneering post-war school design was recognised as early as 1971 when it became a Grade II listed building.

Richmond High School

In 1938 Denis produced a report on production methods in housing that, in 1941, led him to join the Committee for the Industrial and Scientific Provision of Housing. He was also one of two architect-members of the Wood Committee, set up by the Ministry of Education in 1943 to consider standardised construction and layouts for the new schools needed after the war. He recognised that a greater austerity of design would follow the war. However, prefabrication proved an impossible ideal, as he quickly realised: primarily because of the difficulty of assembling large numbers of elements from different sources. In consequence, his ideas returned to more conventional methods of construction.

After World War II, he restarted his practice in a warehouse at 6 Mason's Yard in St James’, London. The Education Act 1944, in which local by-laws were changed, made every school in the country obsolete. New schools were desperately needed and there was a lack of architects and the skilled workforce to build them. Standard industrial practice couldn’t cope: buildings were thrown up without reference to architects and there was also a desperate shortage of materials. Denis used his ingenuity to adapt or recycle materials for new schools in Ormesby and Greenwich; designing trusses for large-span spaces with T-sections and bent rebar for diagonals.

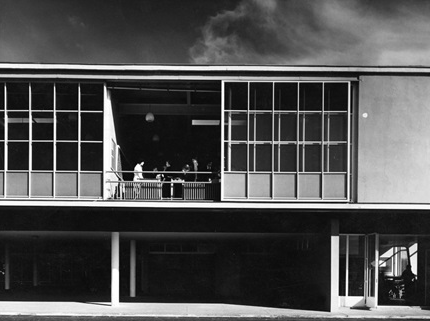

His most ambitious post-war secondary school was that at Cranford in Middlesex, which in 1950-53, introduced a strikingly compact and economical square plan that was very different from the Richmond Girls' High School.

In 1950, he was also the sole assessor for the renowned Hunstanton School competition won by Alison & Peter Smithson. Against strong local opposition, he championed their rigidly symmetrical design. Whereas all the other entries were essential copies of Denis’ previous schools, the Smithsons’ design was the only one that took school design forward. He fought for their design despite the objections of the local councillors. The Smithsons’ project was nearly thrown out over poor costings but Denis proved their scheme was viable and they were duly awarded the contract.

With more and more new schools to do, he opened a satellite office in Lincoln in 1954, which was headed-up Sam Scorer (who had recently joined him from the AA). Between 1948 and 1973 he and Scorer designed 27 schools for 11 different local authorities. They also developed a system of top-lighting for Middlesex County Council, the principals of which were subsequently adopted by the Government as a requirement for natural lighting in all schools.

Denis’s last great school was again in Richmond. It was a secondary modern school on a tight sloping site, with the compact plan, lending itself to a bar-like structure set perpendicular to the contours, with classrooms on the top and larger spaces tucked underneath as the landscape fell away.

Aside from his many school designs, Denis also designed housing schemes in Hornchurch and near St. Pancras Station, as well as civic centres in Egham and Cranbrook. He was proud that all these buildings were directly commissioned and that after the 1937 News Chronicle competition, he never again had to enter a competition to win work.

Richmond School (1960)

Richmond School (1960)

Richmond School (1960)

Richmond School (1960)

Richmond School (1960)

Woodfield Secondary Modern (1954)

Woodfield Secondary Modern (1954)

Woodfield Secondary Modern (1954)